Provoke, Motivation, and Finally Following Through

This post picks up where my last journal entry left off—somewhere between feeling inspired and actually doing something about it.

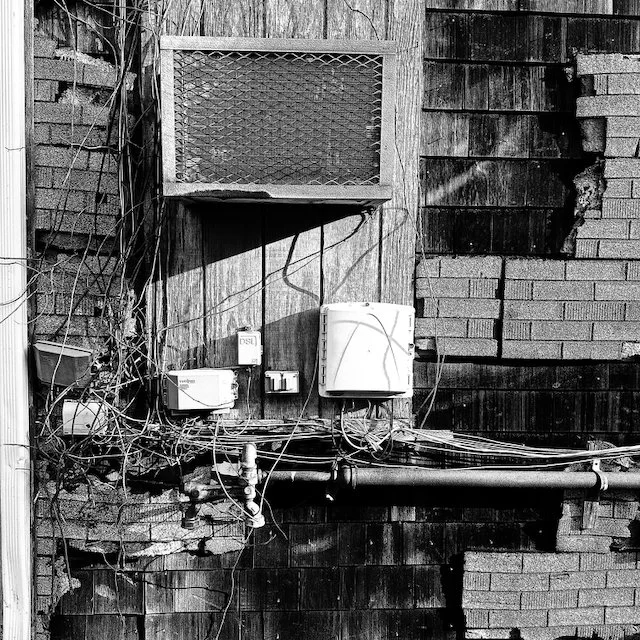

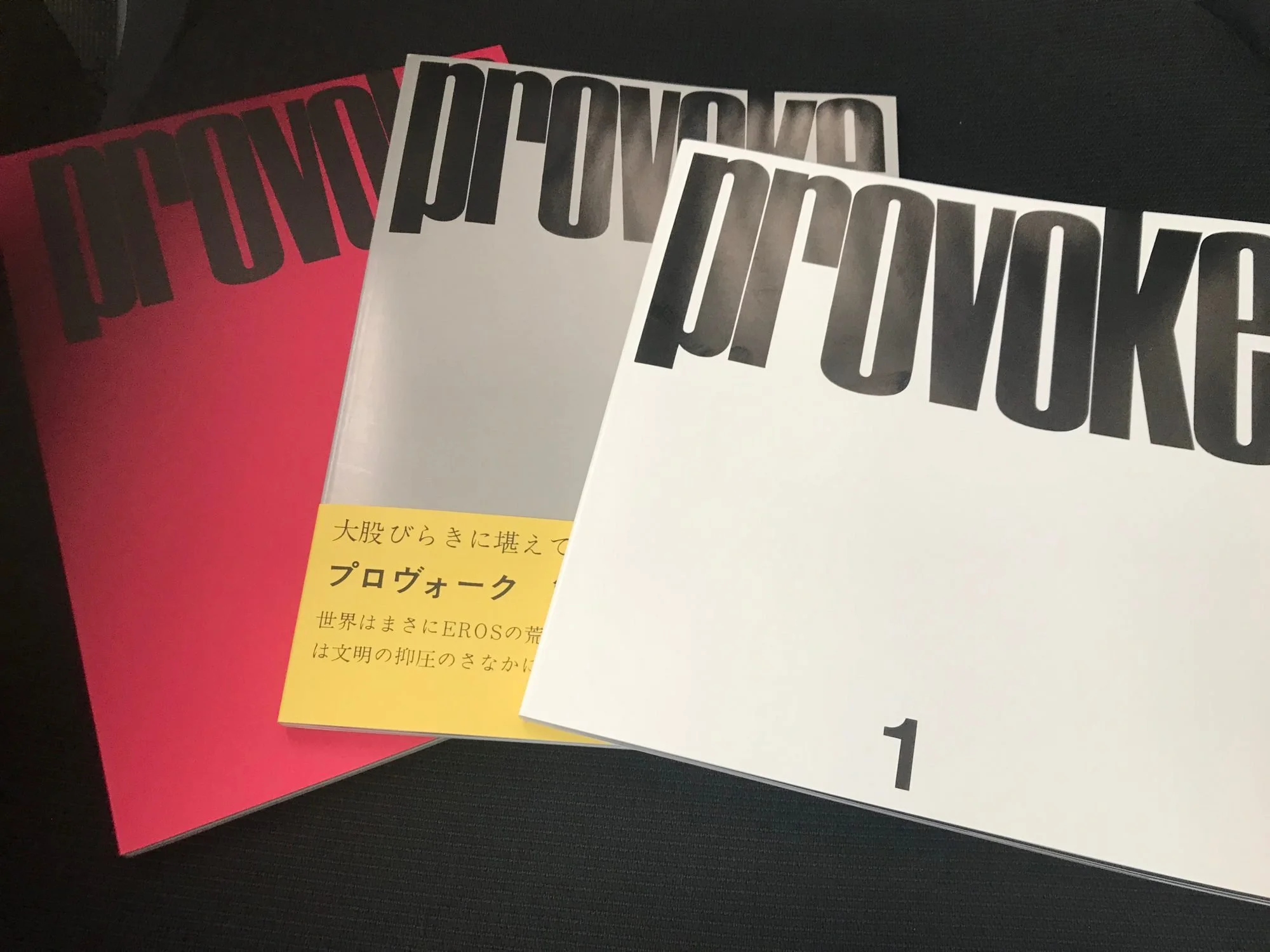

At the end of my last journal post, I wrote that I was feeling inspired. The funny thing about inspiration, though, is that without motivation and focus, it doesn’t amount to much. Ideas pile up, and nothing actually happens. After sitting with it for a while, I’ve finally found the motivation to follow through. In that last post, I shared a series of images made with the Provoke iPhone app. I’ve been an admirer of Diado Moriyama for a long time—his raw, high‑contrast black‑and‑white street photographs have stuck with me for years. Moriyama is often associated with the avant‑garde photography magazine Provoke (starting to see the connection?). I own a number of his books—nowhere near a complete run, considering his bibliography lists more than 175 titles—but enough that his influence has slowly worked its way into how I think about photographs. Reading about his work eventually led me straight to Provoke itself.

Provoke magazine was launched in 1968 by Takuma Nakahira, Yutaka Takanashi, and critic Koji Taki, with Moriyama joining for issue #2. Japan at the time was in the middle of mass and violent political protests, cultural shifts, and a general sense of instability. The founders of Provoke weren’t interested in explaining any of it neatly. Instead of clean, objective documentary work, they pushed photography somewhere rougher and more personal—almost confrontational. The style that emerged became known as are‑bure‑boke—“grainy, blurry, out‑of‑focus.” And that wasn’t an accident. They shot fast and loose, printed hard for contrast, embraced blur, and let imperfections stay in the frame. The images feel restless and unresolved, more like fragments of lived experience than carefully finished statements.

That’s exactly what I respond to in the Provoke app. It doesn’t reward precision so much as instinct. In a world where smartphone cameras keep promising sharper, cleaner, more technically perfect images, there’s something refreshing—almost liberating—about an approach that basically says: don’t overthink it, just shoot. This is why I keep coming back to this era of Japanese photography. It reminds me that photography can be fun, raw, emotional, and imperfect—and still absolutely worth pursuing.

Lately, the Provoke app has been essential in helping me work through a lingering sense of discontent and frustration with my own photographic practice. When things start to feel stalled or overly self-critical, shooting with this app gives me permission to loosen my grip, to make photographs without expectations, and to reconnect with the simple act of seeing. Using it on my phone brings a little of that Provoke-era energy into everyday shooting, even in the most ordinary places.

Sidebar: Are‑Bure‑Boke — Then and Now

Are‑bure‑boke literally translates to grainy, blurry, out‑of‑focus, but it’s more than just a look. In the late 1960s, it was a deliberate rejection of the classical Western photographic values that came before it—clarity, objectivity, and visual polish. At the time, Japanese critics were sharply divided. Some dismissed Provoke photography as chaotic, irresponsible, or even nihilistic, arguing that it abandoned photography’s social and communicative role. Others—especially critics aligned with Provoke—believed traditional photographic language had failed, and that breaking it apart was the only honest response to the moment.Looking back, are‑bure‑boke is now widely seen as a turning point: photography not as explanation, but as experience. Provoke magazine ultimately lasted for just three issues, but its influence was profound and the are‑bure‑boke style it introduced that once felt confrontational and unsettling has gone on to influence generations of photographers worldwide.